Debre Bizen is the best-known monastery of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Located at the top of Debre Bizen the mountain (825 meters) is near the town of Nefasit in Eritrea. Its library contains many important Ge’ez manuscripts. The monastery is actually a small village of a few dozen stone monk’s houses, three churches, some classrooms, and agricultural support buildings. Debre Bizen homes some 60 monks, who chose to live an austere life, and a fluctuating number of students in its religious school. They are the custodians of Debre Bizen’s collection of more than 1,000 medieval manuscripts, including finely illustrated parchments bound in thick leather, cloth, and wood.

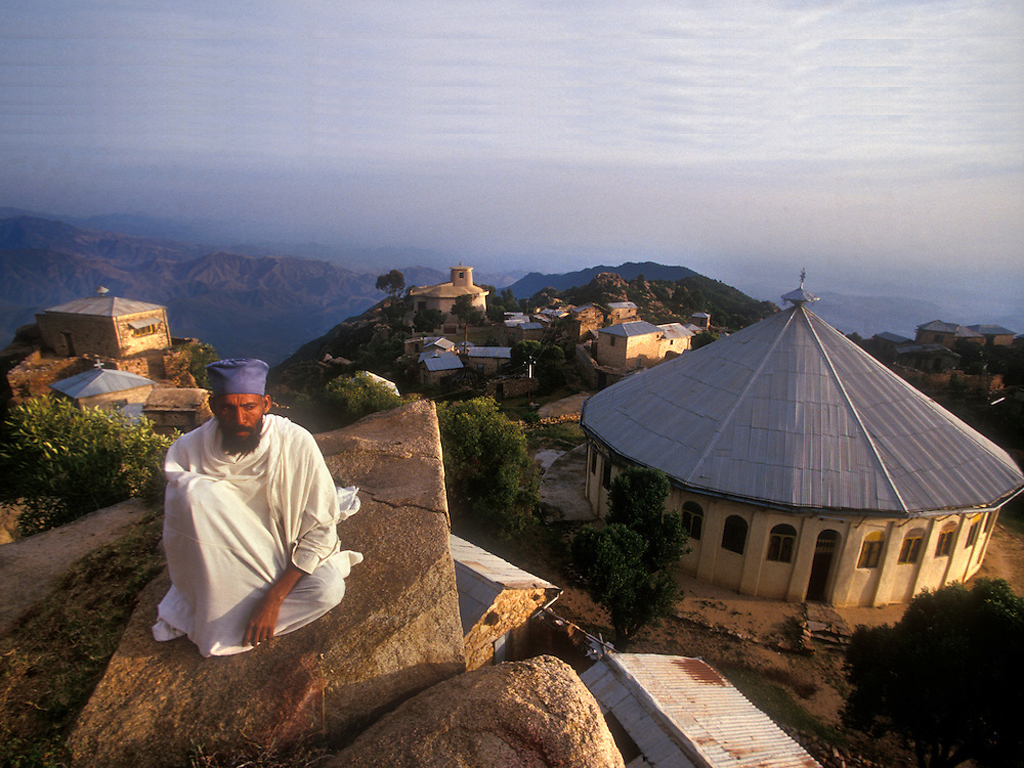

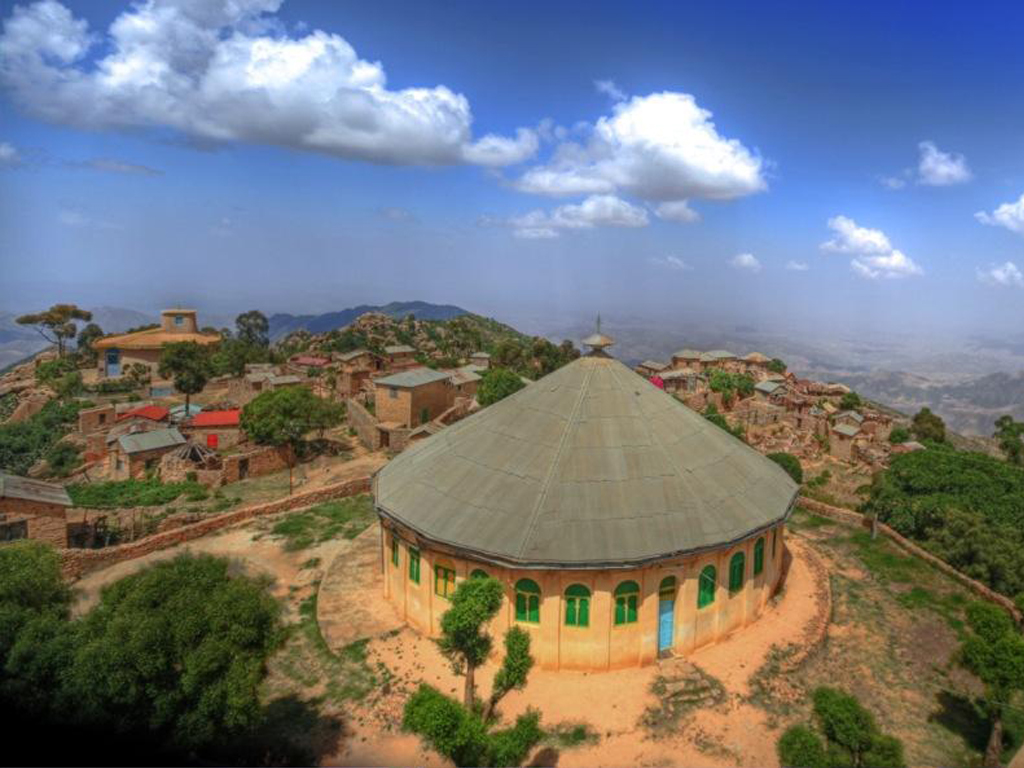

The spot commands magnificent views of the surrounding hills and all the way down to the line of the Red Sea coast. The atmosphere of the settlement, surrounded by a grove of rare indigenous trees, is pious and medieval, other-worldly and even magical. At night the lights of Massawa sparkle in the distance. On the day the air is cool, there are birds singing and green grass grows between the monastery buildings. At dawn, a carpet of glistening white cloud often hides the earth below where the village of Nefasit with its yellow and green-domed mosques and a Coptic church nestles at the base of the mountain. The views to the sea and Dahlak Islands, to the Buri Peninsula and the Gulf of Zula, and south to the mountains of Akele Guzai, are the most impressive in Eritrea.

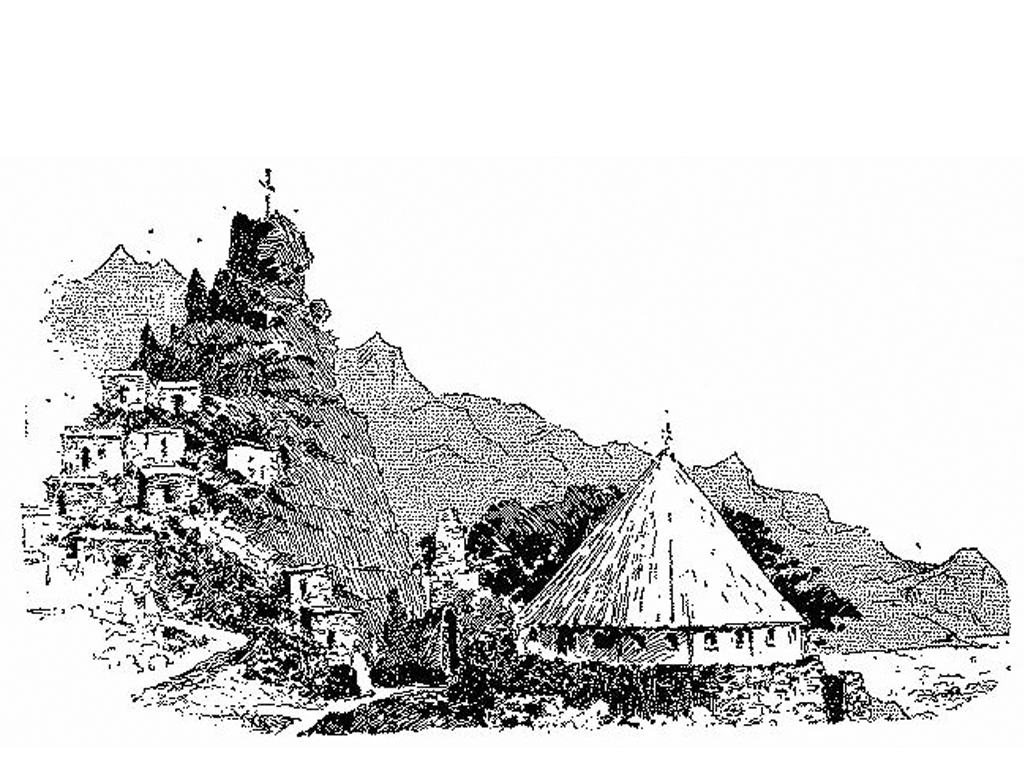

The Debre Bizen Monastery is the most prominent beacon and symbol of Christianity in Eritrea, wrapped in legend and history. Perched on a mountain at a pinnacle of 2450 meters above sea level, the Monastery of Debre Bizen was founded by His Holiness Abune Filipos, a student of Abune Tatyos, in 1361 AD. Legend has it that his shadow allegedly cured three cripples due to his sheer holiness.

His teacher, Tatyos, is also the subject of legend. During his evangelical journey eastwards, he asked a captain to take him across the Red Sea. The captain asked for money, but Tatyos therefore resorted to sitting on his cloak, which bore him up like a magic carpet and flew him across the seas and deserts to Armenia. He supposedly launched himself from a rocky ledge, north of the monastery, called Adey Kbetsni, ‘Goodbye My Mother‘. It is claimed that the gnarled tree which stands on the wind-blown rock today is one that bowed down to the pious monk as he prepared to launch himself into the skies. Behind the outcrop, Adey Kbetsni, is a tomb dedicated to Abune Yohannes, an abbot of the monastery who lived five hundred years ago.

The monastery is a collection of pink granite buildings cut into the sides of huge smooth rocks. The oldest building is the church built during the lifetime of monk Filipos, on top of the roof is an intricate Orthodox crucifix and circle of bells, which jangle in the breeze. The walls of the church are painted yellow with decorated wooden shutters and doors. For centuries it has survived as a center of Christian prayer and learning in spite of invading armies and religious conflict from that of Somali hordes of Ahmed Gragn to the Derg.

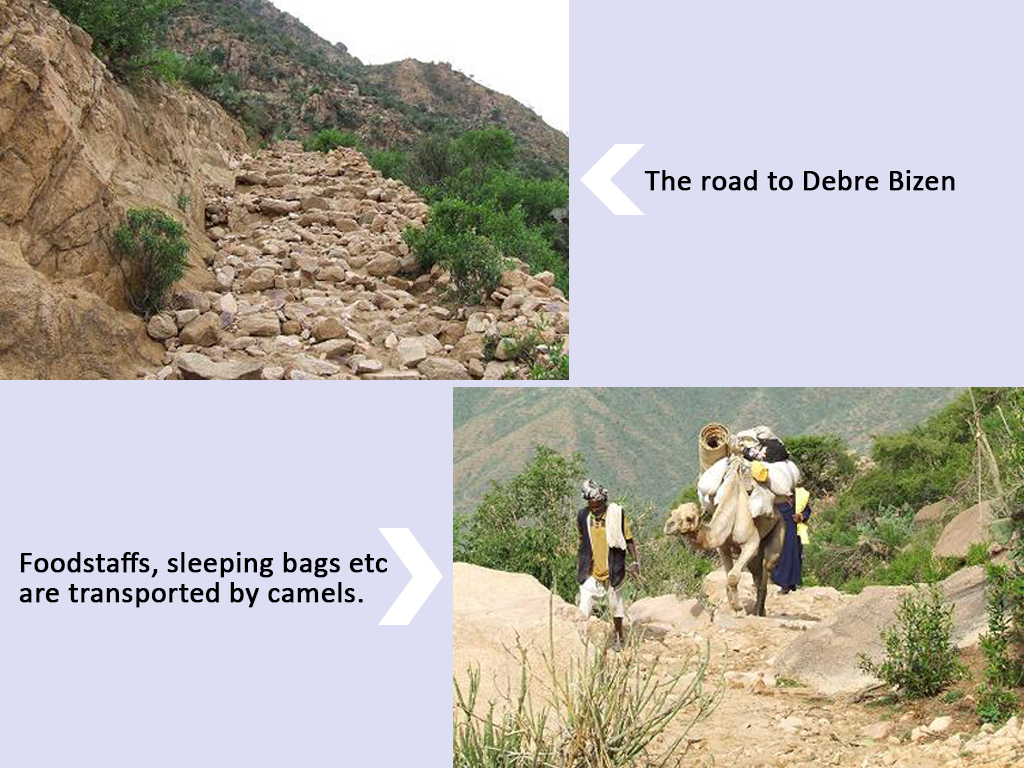

Once very prosperous, most of the monastery’s property was confiscated during the time of the Dergue’s occupation, which actively discouraged religious institutions The Dergue’s culture commissars told the monks that religious artifacts should be burned. During the Dergue regime, the monastery was used as a military base to keep watch over the surrounding region. Today the only invaders are a family of baboons who regularly raid the monastery’s meager food supplies brought up the mountain by donkeys and camels.

In the compound are species of African olives that look very similar to the European and Middle Eastern kind cultivated for oil export but they are species growing quite wild.

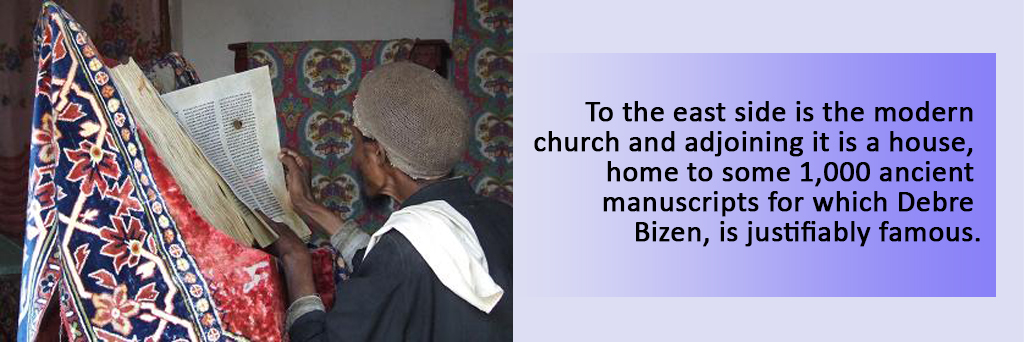

To the east is the modern church and adjoining it is a house, home to some 1,000 ancient manuscripts for which Debre Bizen, is justifiably famous. Several dozen fine illuminated parchments bound in thick leather, cloth, and even wood, are stacked in this archive. Some of these manuscripts include the most extraordinary Bible dating back to the 14th century, to the time of Filipos. Another exquisite manuscript is the lost biblical Book of Enoch, and a third is the story of Abune Libanos, a great churchman who traveled from Lebanon and found the monastery of Debre Libanos in Eritrea’s southern highlands. The manuscripts are examples of the finest medieval workmanship, meticulously written in the liturgical language of Ge’ez in red or black inks with elaborate illuminations. A bell is rung whenever a manuscript is removed from the library, which is rare because monks tend to read on the spot. It also has a collection of embroidered ecclesiastical robes and umbrellas, wooden carved crosses, and other artifacts.

Perhaps the most fascinating history of Debre Bizen is that it has devised its own calendar, invented by a certain monk called Gebremekel and known as Hasabe Bizen (The Thinking of Bizen). It has 35 columns and was based on Hebrew and Christian calendars. The dating started from the creation of the earth and ended at the year 1500AD because the inventor believed that the year 1500AD would be doomsday or the end of the world. The calendar has not been used since 1500AD; as such it lags 236 years behind the Gregorian calendar. Had it been in use, now the year according to Bizen Calendar or The Thinking of Bizen would be 1782.

It is possible for men to visit the monastery, but the only way to make the 825 meters, 7km climb to the top is on foot (which takes, depending on your condition, between one and a half and three hours). The reward for those who endure the grueling climb is a spectacular view of the surrounding barren mountains. The Red Sea, some 80 kilometers distant, is visible from here on a clear day.

The sign says “No females beyond this point. Of any species. Turn back now.” Women are denied entrance to the monastery and its surroundings. This rule applies also to female pack animals (!)Birds are excepted from this rule for practical reasons, and hens are allowed for the production of eggs. Abune Phillipos wanted to avoid the distractions of local girls. Abune Phillipos is rumored to have said that he would “rather stare into the face of a lion than into a woman’s eyes.”

The best time to make the climb is in the early morning and return in the late afternoon. It is customary to leave the monks a contribution to aid in the maintenance and reconstruction of the monastery.

The annual celebration of Bizen Monastery falls on August 11.

Along the steep path, a large cross marks the point at which women must stop and proceed no further. This rule is taken to great lengths and not even female animals are allowed near, meaning only mules and male donkeys are used as pack animals. Debre Bizen Monastery was founded by Abune Filipas to protect his monks from ‘the temptation of women’. Legend has it that Filipos moved the Coptic religious community up the mountains from Nefasit because he preferred the roar of lions- which at that time inhabited the wild mountains- to the distraction of women’s faces.

The monks, who today number more than 100, live in an egalitarian society, wearing the same clothes and eating the same food whatever their rank. They also offer a charitable refuge for handicapped, old, and destitute men. They survive on rainwater collected off the guttering of the roofs and use solar power cells to generate electricity to run their light bulbs.

The blackened interior of the kitchen is an impressive place, containing vast copper pots which are large enough to cook three cattle at once. And indeed a huge amount of cooking is done during the festival at the monastery. A sorghum beer called Suwa is also brewed for these occasions in a stone congress hall next to the kitchen. In another neighborhood, the hall is a large timber used as stock for punishing wrongdoers in the monastery.

Pilgrims and visitors are housed in a guesthouse with arched doors. Outside is a trough carved out of a huge stone which the monks’ claim was carried on the back of one of Filipos` pupils. Today it is used for bread-making.

Practically reality combined with piety, myth a mystery make Debre Bizen a unique religious retreat. And as one gazes across the crumpled folds of craggy mountain monastery, it is not difficult to believe that it will continue to survive unscathed for many more centuries.

Sources: